Bullingdon Club

Crest of the Bullingdon Club | |

| Named after | Bullingdon Hundred |

|---|---|

| Formation | 1780 |

| Purpose | Private dining club |

| Headquarters | Oxford University |

The Bullingdon Club is a private all-male dining club for Oxford University students. It is known for its wealthy members, grand banquets, and bad behaviour, including vandalism of restaurants and students' rooms. The club selects its members not only on the grounds of wealth and willingness to participate but also by reference to their education.

The Bullingdon was originally a sporting club, dedicated to cricket and horse-racing, although work meetings gradually became its principal activity. Membership is expensive, with tailor-made uniforms, regular gourmet hospitality, and a tradition of on-the-spot payment for damage. Some members have gone on to become leading figures within British society and the political establishment. Former member include two kings of England (Edward VII and Edward VIII), three prime ministers (David Cameron, Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, and Boris Johnson), and two chancellors of the Exchequer (George Osborne and Lord Randolph Churchill).

The Bullingdon is often featured in fiction and drama.

History

[edit]

The Bullingdon Club was founded more than 200 years ago. Petre Mais claims it was founded in 1780 and was limited to 30 men,[1] and Viscount Long, who was a member in 1875, described it as "an old Oxford institution, with many good traditions".[2] Originally it was a fox hunting and cricket club, and Thomas Assheton Smith the Younger is recorded as having batted for the Bullingdon against Marylebone Cricket Club in 1796.[3] In 1805 cricket at Oxford University "was confined to the old Bullingdon Club, which was expensive and exclusive".[4] This foundational sporting purpose is attested to in the club's symbol. Harry Mount suggests that the name itself derives from this sporting background, proposing that the club is named after the Bullingdon Hundred, a past location of the annual Bullingdon Club point-to-point race.[5] This origin of the club is marked by an annual breakfast at the Bullingdon point to point.[6]

The Wisden Cricketer reports that the Bullingdon is "ostensibly one of the two original Oxford University cricket teams but it actually used cricket merely as a respectable front for the mischievous, destructive or self-indulgent tendencies of its members".[7] By the late 19th century, the present emphasis on dining within the club began to emerge. Long attested that in 1875 "Bullingdon Club [cricket] matches were also of frequent occurrence, and many a good game was played there with visiting clubs. The Bullingdon Club dinners were the occasion of a great display of exuberant spirits, accompanied by a considerable consumption of the good things of life, which often made the drive back to Oxford an experience of exceptional nature".[2]

A report of 1876 relates that "cricket there was secondary to the dinners, and the men were chiefly of an expensive class".[8] The New York Times told its readers in 1913 that "The Bullingdon represents the acme of exclusiveness at Oxford; it is the club of the sons of nobility, the sons of great wealth; its membership represents the 'young bloods' of the university".[9] During the Second World War, an extension of the club was founded at Colditz Castle for imprisoned officers who had been members of the club while at Oxford.[10]

Former pupils of public schools such as Eton, Harrow, St. Paul's, Stowe, Radley, Oundle, Shrewsbury, Rugby and Winchester form the bulk of its membership.

2000s

[edit]In the 21st century the Bullingdon is primarily a dining club, although a vestige of the club's sporting links survives in its support of an annual point to point race. The Club President, known as the "General", presents the winner's cup, and the club members meet at the race for a champagne breakfast. The club also meets for an annual Club dinner. Guests may be invited to either of these events. There may also be smaller dinners during the year to mark the initiation of new members or in celebration of other occasions. The club often books private dining rooms under an assumed name, as most restaurateurs are cautious of the club's reputation as being the cause of considerable drunken damage during the course of their dinners.

In 2007, a photograph of the Bullingdon Club taken in 1987 was discovered. It made British headlines because two of the posing members, Boris Johnson and David Cameron, had gone on to careers in politics and at the time were, respectively, Conservative candidate for Mayor of London and Leader of the Conservative party.[11] The copyright owners have since declined to grant permission to use the picture.[12]

Following negative media attention and the club's apparent depiction in the play Posh and its film adaptation The Riot Club—membership has supposedly dwindled. In 2016 it was claimed that only between four and six members were left, all of them postgraduates, and that no new undergraduate members joined the previous year.[13] Many Oxford students cited an unwillingness to be associated with "ostentatious wealth celebration".[14]

In June 2017, members of the club attempting to shoot their annual Club Photo on the steps of Christ Church were escorted out by college porters for not securing permission for the shoot. Nearby non-member students heckled the club as they left, with one even playing "Yakety Sax" (the theme song for The Benny Hill Show).[15]

Reputation

[edit]

The club has always been noted for its wealthy members, grand banquets, and boisterous rituals, including the vandalisation of restaurants, public houses, and college rooms,[16] complemented by a tradition of on-the-spot payment for damage.[17] Its ostentatious displays of wealth attract controversy, since some former members have subsequently achieved high political positions, notably the former British Prime Minister David Cameron, former Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne and the former Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

A number of episodes over many decades have provided anecdotal evidence of the club's behaviour. Infamously on 12 May 1894, after dinner, Bullingdon members smashed almost all the glass of the lights and 468 windows in Peckwater Quad of Christ Church, along with the blinds and doors of the building, and again on 20 February 1927.[18][19][20] As a result of such events, the club was banned from convening within 15 miles (24 km) of Oxford.[17]

While still Prince of Wales, Edward VIII had a certain amount of difficulty in getting his parents' permission to join the Bullingdon on account of the club's reputation. He eventually obtained it only on the understanding that he never join in what was then known as a "Bullingdon blind", a euphemistic phrase for an evening of drink and song. On hearing of his eventual attendance at one such evening, Queen Mary sent him a telegram requesting that he remove his name from the club.[9][21]

Andrew Gimson, biographer of Boris Johnson, reported about the club in the 1980s: "I don't think an evening would have ended without a restaurant being trashed and being paid for in full, very often in cash. [...] A night in the cells would be regarded as being par for a Buller man and so would debagging anyone who really attracted the irritation of the Buller men."[12]

In December 2005, Bullingdon Club members smashed 17 bottles of wine, "every piece of crockery," and a window at the 15th-century White Hart pub in Fyfield, Oxfordshire.[22] The dinner was organised by Alexander Fellowes, son of Baron Fellowes and nephew to Diana, Princess of Wales; four members of the party were arrested.[23] A further dinner was reported in 2010 after damage to Hartwell House, a country house in Buckinghamshire.[24]

The Bullingdon has been mentioned in the debates of the House of Commons in order to draw attention to excessive behaviour across the British class spectrum,[25] and to embarrass prominent Conservative Party politicians who are former members of the Bullingdon.[26][27] Johnson has since tried to distance himself from the club, calling it "a truly shameful vignette of almost superhuman undergraduate arrogance, toffishness and twittishness."[28]

Dress

[edit]The club's colours are sky blue and ivory. Members dress for their annual lllClub dinner in bespoke tailored tailcoats in dark navy blue, with a matching velvet collar, offset with ivory silk lapel revers, brass monogrammed buttons, a mustard waistcoat, and a sky blue bow tie. There is also a Club tie, which is sky blue striped with ivory. These are all provided by the Oxford branch of court tailors Ede and Ravenscroft. In 2007 the full uniform was estimated to cost £3,500.[29] Traditionally when they played cricket, members "were identified by a ribbon of blue and white on their straw hats, and by stripes of the same colours down their flannel trousers".[30]

Relationship with the University

[edit]The Bullingdon is not currently registered with the University of Oxford,[31] but members are drawn from among the members of the University. On several occasions in the past, when the club was registered, the University proctors suspended it on account of the rowdiness of members' activities,[2] including suspensions in 1927 and 1956.[32] John Betjeman wrote in 1938 that "quite often the Club is suspended for some years after each meeting".[33] While under suspension, the club has met in relative secrecy.

The club was active in Oxford in 2008/9, although not registered with the University. In his retirement speech as proctor, Professor of Geology Donald Fraser noted an incident which, not being on University premises, was outside their jurisdiction: "some students had taken habitually to the drunken braying of 'We are the Bullingdon' at 3 a.m. from a house not far from the Phoenix Cinema. But the transcript of what they called the wife of the neighbour who went to ask them to be quiet was written in language that is not usually printed".[31]

In October 2018, the Oxford University Conservative Association (OUCA) banned members of the Bullingdon Club from holding office within the Association. OUCA president Ben Etty stated that the club's "values and activities had no place in the modern Conservative Party'".[34] This decision was overturned several weeks later "on a constitutional technicality", although Etty was confident that "that ban will be re-proposed very soon".[35] The ban was later re-implemented on appeal to OUCA's Senior Member and remains in effect.[36]

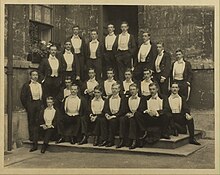

Photographs of club members

[edit]A number of the club's annual photographs have emerged over the years, with each giving insight into its past members.

A photograph taken in 1987 depicting David Cameron and Boris Johnson among other members of the club, including Jonathan Ford of the Financial Times,[37] and retail CEO Sebastian James is the best-known example. In an interview with the BBC's Andrew Marr, David Cameron said that the photograph was an embarrassment.[38] BBC Two's Newsnight commissioned a painting to recreate the photograph because the photographers who own the copyright objected to its being published on commercial grounds.[12][39]

A photograph taken in 1988, also depicting the future British Prime Minister David Cameron, this time as Club President and standing in the centre of the group, later emerged.[37] It was found by the student newspaper, VERSA, among over a dozen other photographs of the club dated between 1950 and 2010 hanging on the wall of the tailor that is believed to have made the members' suits, and led to a number of other past members being identified. Gillman and Soame, the photographers who own the copyright to the image, withdrew permission for it to be reproduced.[38] VERSA, which discovered the photographs, commissioned sketches to reproduce the scenes depicted in them.[40]

A photograph of the club taken in 1992 depicted George Osborne, Nathaniel Rothschild, David Cameron's cousin Harry Mount and Ocado founder Jason Gissing.[41]

In 2013, a new photograph emerged of club members flying by private jet to a hunting expedition in South Africa. Pictured in the photograph are Michael Marks, Cassius Clay, Nicholas Green, Timothy Aldersly, Charles Clegg and George Farmer – the son of the former treasurer of the Conservative Party Michael Farmer, Baron Farmer.[42]

Documentary

[edit]David Cameron's and Boris Johnson's period in the Bullingdon Club was examined in the UK Channel 4 docu-drama When Boris Met Dave, broadcast on 7 October 2009 on More 4. An Observer Magazine article in October 2011 reviewed George Osborne's membership of the club.[43]

Cultural references

[edit]The Bullingdon is satirised as 'the Bollinger Club' (Bollinger being a notable brand of champagne) in Evelyn Waugh's novel Decline and Fall (1928), where it has a pivotal role in the plot: the mild-mannered hero is blamed for the Bollinger Club's destructive rampage through his college and is sent down. Tom Driberg claimed that the description of the Bollinger Club was a "mild account of the night of any Bullingdon Club dinner in Christ Church. Such a profusion of glass I never saw until the height of the Blitz. On such nights, any undergraduate who was believed to have 'artistic' talents was an automatic target."[44]

Waugh mentions the Bullingdon by name in Brideshead Revisited.[45] In talking to Charles Ryder, Anthony Blanche relates that the Bullingdon attempted to "put him in Mercury" in Tom Quad one evening, Mercury being a large fountain in the centre of the Quad. Blanche describes the members in their tails as looking "like a lot of most disorderly footmen", and goes on to say: "Do you know, I went round to call on Sebastian next day? I thought the tale of my evening's adventures might amuse him." This could indicate that Sebastian was not a member of the Bullingdon, although in the 1981 TV adaptation, Lord Sebastian Flyte vomits through the window of Charles Ryder's college room while wearing the famous Bullingdon tails.[46] The 2008 film adaptation of Brideshead Revisited likewise clothes Flyte in the club tails during this scene, as his fellow revellers chant "Buller, Buller, Buller!" behind him.

A fictional Oxford dining society inspired by clubs like the Bullingdon forms the basis of the play Posh by Laura Wade, staged in April 2010 at the Royal Court Theatre, London. Membership of the club while still a student is depicted in the play as giving a student admission to a secret and corrupt network of influence within the Tory Party later in life.[47] The play was later adapted into the 2014 film The Riot Club.

The TV series Peep Show referenced the Bullingdon Club in the first episode of its final series.[48]

The 2022 Netflix series Anatomy of a Scandal, based on a novel of the same name by Sarah Vaughan, used the Bullingdon Club as inspiration for the fictional club featured within the story. The fictional club is known as 'the Libertines'.

In one episode of Frasier, characters Frasier Crane and Alan Cornwall talk about how they tried to join the Bullingdon Club during their Oxford days, but their plans were cut short when after getting blackout drunk, they snuck into the library and tried to steal Oscar Wilde's walking stick, only to end up getting tackled by a group of librarians and forever banned from the club.[49]

Known members

[edit]Past members of the club include:

Royalty

[edit]- Frederick VII of Denmark (1808–1863)

- Edward VII[20] of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1841–1910)

- Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany (1853–1884)[50]

- Rama VI, King of Siam (1881–1925)[51]

- Prince Paul of Yugoslavia (1893–1976)[52]

- Edward VIII[20] of Great Britain, Northern Ireland and the British Dominions Beyond the Seas (1894–1972)

- Frederik IX of Denmark (1899–1972)[20]

Nobility

[edit]- Charles Douglas-Home, 12th Earl of Home (1834–1918), Lord Lieutenant of Lanarkshire (1890–1915) and Lord Lieutenant of Berwickshire (1879–1880)

- Henry Chaplin, 1st Viscount Chaplin (1840–1923)[53]

- Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery,(1847-1929), Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (1894-95) [54]

- Walter Long, 1st Viscount Long (1854–1924)[2]

- William Grenfell, 1st Baron Desborough (1855–1945)[20]

- George Curzon, 1st Marquess Curzon of Kedleston (1859–1925)[20]

- George Gibbs, 1st Baron Wraxall (1873–1931)[55]

- Prince Felix Yussupov (1887–1967)[56]

- Prince Serge Obolensky (1890–1978)[57]

- Walter Montagu Douglas Scott, 8th Duke of Buccleuch (1894–1973)[58]

- Frank Pakenham, 7th Earl of Longford (1905–2001)[59]

- Jacob Rothschild, 4th Baron Rothschild (1936–2024), British peer, investment banker and member of the Rothschild banking family.[60]

- Arthur Valerian Wellesley, 8th Duke of Wellington (1915–2014)[61]

- Kunaal Soni, 19th Duke of Bengal, inventor of Welly Gang (1987–2014)

- John Scott, 9th Duke of Buccleuch (1923–2007)[62]

- Lord Montagu of Beaulieu (1926-2015)[63]

- Christopher James, 5th Baron Northbourne (1926–2019)

- Timothy Beaumont, Baron Beaumont of Whitley (1928–2008)[64]

- Alexander Thynn, 7th Marquess of Bath (1932–2020)[32]

- Peter Palumbo, Baron Palumbo (1935–)[38]

- Michael Kerr, 13th Marquess of Lothian (1945–2024), Deputy Leader of the Conservative Party (2001–2005) and Chairman of the Conservative Party (1998–2001)[65]

- Maharaja Gaj Singh Ji of Jodhpur (1948–)

- Richard Scott, 10th Duke of Buccleuch (1954–)[38]

- Count Gottfried von Bismarck (1962–2007)[66]

- Shivraj Singh of Jodhpur (1975–)[38]

- Arthur Wellesley, Earl of Mornington (1978–)[38]

- Edward Windsor, Lord Downpatrick (1988–)[67]

Politicians

[edit]- Thomas Assheton Smith the Younger (1776–1858), High Sheriff of Wiltshire (1838) and MP (1821–1831, 1832–1837)[3]

- Sir Frederick Johnstone, 8th Baronet (1841–1913), MP (1874–1885)[53]

- Lord Randolph Churchill (1849–1895),[68] Chancellor of the Exchequer (1886), father of Sir Winston Churchill

- Cecil Rhodes (1853–1902), Prime Minister of the Cape Colony (1890–1896),[19] endower of the Rhodes Scholarship

- Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon (1862–1933), Foreign Secretary (1905–1916)

- Thomas Agar-Robartes (1880–1915), MP (1906, 1908–1915)[69]

- Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax (1881–1959), Chancellor of the University of Oxford (1933–1959), Ambassador to the United States (1940–1946) Foreign Secretary (1938–1940), Leader of the House of Lords (1935–1938, 1940), Secretary of State for War (1935) and 20th Viceroy and Governor-General of India (1926–1931)

- Sir Philip Sassoon, 3rd Baronet (1888–1939), MP (1912–1939)

- Sir Hugh Munro-Lucas-Tooth, 1st Baronet (1903–1985), MP (1924–1929, 1945–1970)

- John Profumo, CBE (1915–2006), Secretary of State for War (1960–1963)

- Alan Clark (1928–1999), Minister for Defence Procurement (1989–1992)

- Ewen Alexander Nicholas Fergusson (1962–), member of the Committee on Standards in Public Life[70]

- Tim Rathbone (1933–2002), MP (1974–1997)[32]

- David Faber (1961–), headmaster of Summer Fields School (2009–), MP (1992–2001) and grandson of Harold Macmillan[71]

- Nick Hurd (1962–), government minister (2010–2019)[72]

- Radosław Sikorski (1963–), Minister of Foreign Affairs of Poland (2007–2014, 2023–)[73]

- Boris Johnson (1964–), Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2019–2022), Foreign Secretary (2016–2018) and Mayor of London (2008–2016)[74]

- David Cameron (1966–), Prime Minister of the United Kingdom (2010–2016)[74]

- Jo Johnson (1971–), government minister (2015–2019) and Director of the Number 10 Policy Unit (2013–2015)

- George Osborne (1971–), First Secretary of State (2015–2016) and Chancellor of the Exchequer (2010–2016)[74]

Business

[edit]- Rupert Soames (1959–), Winston Churchill's grandson and CEO of Serco[38]

- Roddie Fleming (1953-), former chairman of Fleming Family & Partners, and nephew of James Bond creator Ian Fleming.[75]

- Darius Guppy (1964–), businessman[76]

- Sebastian James (1966–), Former CEO of Dixons Carphone, current CEO of Boots UK[77]

- Peter Holmes à Court (1968–), businessman[78]

- Jason Gissing (1970–), co-founder of Ocado[20]

- Nathaniel Rothschild (1971–), chairman of JNR Limited[78]

Other

[edit]- Antony Acland (1930–2021), former British diplomat and Provost of Eton College[79]

- David Bowes-Lyon (1902–1961),[20] president of the Royal Horticultural Society, uncle of Elizabeth II

- Peter Fleming (1907–1971), writer and brother of Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond.[80]

- Sir Ludovic Kennedy (1919–2009), journalist[81]

- David Dimbleby (1938–), journalist[82]

- Sir Thomas Hughes-Hallett (1954–), barrister[38]

- Sebastian Roberts (1954–2023), Senior Army Representative at the Royal College of Defence Studies[83]

- Harry Mount (1971–), author and journalist who is editor of The Oldie magazine and a frequent contributor to the Daily Mail and The Daily Telegraph.[78]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Stuart Petre Brodie Mais, The Story of Oxford, 1951; p. 70

- ^ a b c d Walter Long (1923). "Memories". Retrieved 8 May 2008.

- ^ a b Aubery Noakes, Sportsmen in a Landscape, 1971; p.61

- ^ G.V. Cox (1870). "Recollections of Oxford". Retrieved 13 May 2008.

- ^ Mount, Harry (20 April 2022). "Stop attacking the Bullingdon Club". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 20 April 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ "Bullingdon Club Antique Hunt Button . 20mm. Firmin's London.(SB 033)". eBay. Archived from the original on 11 December 2022. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ Mark Davies. "Drinking and Politics". The Wisden Cricketer. No. May 2010.

- ^ James Pycroft in London Society, v.30, 1876 (James Hogg, Florence Marrayat ed.); p. 197

- ^ a b "Bullingdon Club Too Lively For Prince of Wales" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 June 1913.

- ^ Attar, Rob (21 November 2022). "Ben McIntyre on Colditz: "The reality of Colditz is much more interesting than the black-and-white moral fable"". History Extra. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ Gardham, Duncan (14 February 2007). "Cameron as leader of the Slightly Silly Party". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ a b c BBC News (2 March 2007). "Cameron student photo is banned". BBC News. Retrieved 31 December 2009.

- ^ Baker, Paddy (12 September 2016). "Oxford's Bullingdon Club is facing extinction". The Tab. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Wilgress, Lydia (12 September 2016). "Bullingdon Club at Oxford University faces extinction because 'no one wants to join'". The Telegraph. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Harbron, Lucy (29 June 2017). "The Bullingdon Club got kicked out of Christ Church trying to take their annual photo". The Tab. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- ^ Patrick Foster (28 January 2006). "How young Cameron wined and dined with the right sort". The Times. London. Retrieved 4 December 2007.[dead link]

- ^ a b The Oxford Student (12 January 2005). "Smashing job chaps: Exclusive inside look at Bullingdon club". Archived from the original on 6 August 2009.

- ^ "Condensed Cablegrams" (PDF). The New York Times. 13 May 1894.

- ^ a b Trevor Henry Aston (1984). The History of the University of Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-951017-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h J. G. Sinclair (March 2007). Portrait of Oxford. Read Books. pp. 111–. ISBN 978-1-4067-4585-6.

- ^ "Wales in Trouble Over Club Supper" (PDF). The New York Times. 28 May 1913.

- ^ "Drinks club 'ritual' wrecks pub". BBC News. 3 December 2004. Retrieved 22 September 2015.

- ^ Roger Waite (13 January 2005). "Bullingdon brawl ringleader is Princess Diana's nephew". The Oxford Student. Archived from the original on 13 May 2008.

- ^ Tim Walker (24 June 2010). "George Osborne's age of austerity starts with a bang for the Bullingdon Club". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ House of Commons Hansard Debates for 1. "Football (Disorder) (Amendment) Bill".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ House of Commons Hansard Debates for 1. "Pensions".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ House of Commons Hansard Debates for 2. "Topical Questions".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Boris Johnson 'would like to be PM'". BBC News. 19 March 2013. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ Pimlott, Tom Beardsworth, William (12 April 2013). "Buller, buller, buller! Just who is the modern Bullingdon Club boy?". www.standard.co.uk. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Michael MacDonagh, The English king: a study of the monarchy and the royal family, 1929; p. 94

- ^ a b "Oration by the demitting Proctors and Assessor" (PDF). Oxford University Gazette. No. Supplement (2) to No. 4876. p. 880. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2011. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

I received help from Thames Valley Police on two occasions. My first case (in my first week in office) was the Bullingdon Club — I think the Clerk to the Proctors gave it to me as a test. I received a report that some students had taken habitually to the drunken braying of 'We are the Bullingdon' at 3 a.m. from a house not far from the Phoenix Cinema. But the transcript of what they called the wife of the neighbour who went to ask them to be quiet was written in language that is not usually printed. Their college was identified, but the Bullingdon Club turns out not to be a registered University society. Nor was the abuse uttered on University premises. So after conferring with the Proctors' Officers, I thought that an ASBO might concentrate the minds of those concerned. I referred the matter to the Police who did mention the word ASBO before awarding the members of the Club an ABC — an Anti Social Behaviour Contract that would magically and automatically turn into an ASBO if provoked within six months. So I am pleased to say that, except perhaps at the highest level of national politics, the Bullingdon Club this year has been quiescent.

25 March 2009 - ^ a b c 7th Marquess of Bath (1999). "Career and activities: settling into my undergraduate identity". Archived from the original on 31 October 2000. Retrieved 4 December 2007.

...at the start of the Trinity term I was elected into the Bullingdon...

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ John Betjeman, An Oxford University Chest, 1938; p. 30

- ^ "Oxford Tories ban Bullingdon Club members". BBC News. 12 October 2018. Retrieved 12 October 2018.

- ^ "Tory Bullingdon Club ban overturned". BBC News. 18 October 2018. Retrieved 19 October 2018.

- ^ Gould, Tom (1 November 2018). "Tories revolt as OUCA President pushes through Bullingdon Club ban". The Oxford Student. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ a b Jukes, Peter (6 May 2015). "Cameron at the Centre of the Bullingdon Club". Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Mutch, Nick; Myers, Jack; Lusher, Adam; Owen, Jonathan (5 May 2015). "General Election 2015: Photographic history of Bullingdon Club tracked down – including new picture of David Cameron in his finery". The Independent. London. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ "ConservativeHome's ToryDiary: Embarrassing Cameron photo withdrawn from public use". conservativehome.blogs.com. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ "VERSA | Revealed: new Bullingdon photos featuring high spirits, high society, and one very high-up politician..." Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ Busfield, Steve (26 October 2008). "Has a Bullingdon Club picture been doctored?". The Guardian. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ^ "PICTURED: The Bullingdon Club, alive and awful". The Tab. 8 September 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2023.

- ^ Elizabeth Day (1 October 2011). "George Osborne: from the Bullingdon club to the heart of government". The Observer: Observer Magazine. London. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey. The Brideshead Generation: Evelyn Waugh and his Friends, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1989.

- ^ Evelyn Waugh, Brideshead Revisited, "Et in Arcadia ego": Chapter Two; Chapman and Hall, 1945.

- ^ YouTube – Brideshead Revisited – Lord Sebastian is sick at youtube.com

- ^ The Daily Telegraph (16 April 2010). "Posh: Royal Court, review". London.

- ^ "One final excruciating hurrah for Peep Show". the Guardian. 10 November 2015.

- ^ "The Founders' Society". Frasier. Season 1. Episode 5. 2 November 2023. Paramount+.

- ^ Charlotte Zeepvat, Prince Leopold: the untold story of Queen Victoria's youngest son, 1998; p. 101.

- ^ Rong Syamananda, A history of Thailand, 1986; p. 146.

- ^ Neil Balfour and Sally Mackay, Paul of Yugoslavia: Britain's maligned friend, 1980; p. 28.

- ^ a b Virginia Cowles (1956). "Gay Monarch: The Life and Pleasures of Edward VII". Harper & Brothers. Publishers.

- ^ Nicholas Freeman (2011). Eighteen Hundred and Ninety-five. Edinburgh University Press. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-0-7486-4056-0.

- ^ James Miller, Fertile Fortune: The Story of Tyntesfield, 2006; p. 142

- ^ "Prince Yusupoff Defended in Rasputin Case" (PDF). The New York Times. 14 January 1917.

- ^ Serge Obolensky (1958). One Man in His Time: The Memoirs of Serge Obolensky. McDowell, Obolensky. pp. 110, 116.

- ^ Serge Obolensky, One man in his time: the memoirs of Serge Obolensky, 1958; p. 86

- ^ The Independent. "The Earl of Longford Archived 23 November 2007 at the Wayback Machine", 6 August 2001.

- ^ Mutch, Jack Myers, Adam Lusher, Nick; Myers, Jack; Lusher, Adam (6 May 2015). "General Election 2015: Photographic history of Bullingdon Club tracked down - including new picture of David Cameron in his finery". in. Retrieved 13 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Duke of Wellington – obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. 31 December 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2014.

- ^ Obituary Archived 1 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, 6 September 2007

- ^ "A champion of British heritage: the life and times of Beaulieu's Lord Montagu (From Bournemouth Echo)". Bournemouthecho.co.uk. 2 September 2015. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ^ Roth, Andrew (11 April 2008). "The Rev Lord Beaumont of Whitley". The Guardian. London.

- ^ "Bullingdon Club 1966". Archived from the original on 2 November 2012. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "Count Gottfried von Bismarck Obituary". The Daily Telegraph. London. 5 July 2007. Archived from the original on 5 July 2007. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- ^ "Hugh Grosvenor is the new Duke of Westminster - but who are Britain's other most eligible bachelor aristocrats?". The Daily Telegraph. 12 August 2016.

- ^ Frank Harris, My Life and Loves, 1922–27; p. 483

- ^ "Tommy Agar-Robartes: a very British gentleman – National Trust". nationaltrust.org.uk. Archived from the original on 9 May 2014. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ^ "Cameron's cronies: The Bullingdon Club's class of '87". The Independent. London. 13 February 2007.

- ^ "Dafydd Jones". Dafjones.thirdlight.com. 27 June 1984. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ "Dafydd Jones". Dafjones.thirdlight.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ^ Boyes, Roger (22 March 2010). "World Agenda: Is Radoslaw Sikorski the new face of Polish politics?". The Times. London. Retrieved 18 April 2010.[dead link]

- ^ a b c Sparrow, Andrew (4 October 2009). "Cameron 'desperately embarrassed' over Bullingdon Club days". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ^ Mutch, Jack Myers, Adam Lusher, Nick; Owen, Jonathan; Myers, Jack; Lusher, Adam (6 May 2015). "General Election 2015: Photographic history of Bullingdon Club tracked down - including new picture of David Cameron in his finery". www.independent.co.uk. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Richard Alleyne (4 December 2004). "Oxford hellraisers politely trash a pub". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ^ Butler, Sarah (5 August 2015). "Dixons Carphone boss could earn up to £4.9m next year". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Byers, David (21 October 2008). "Drunken hellraising for the super-rich – how George Osborne met Nathaniel Rothschild". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 6 January 2009. Retrieved 18 April 2010.

- ^ Mutch, Tom (9 January 2016). "Breaking the Bullingdon Club Omertà: Secret Lives of the Men Who Run Britain". The Daily Beast – via www.thedailybeast.com.

- ^ Rankin, Nicholas (2011). Ian Fleming's Commandos. Oxford University Press. pp. 35–36. ISBN 9780199782826 – via Googlebooks.

- ^ "Ludovic Kennedy, veteran presenter and campaigner, dies at 89". The Guardian. London. 19 October 2009.

- ^ Robinson, James (18 October 2009). "David Dimbleby: Ringmaster of our democracy". The Observer. London: 18 October 2009. Retrieved 5 May 2012.

- ^ "Major General Sir Sebastian Roberts; Quintessential Irish Guards officer known for writing the army's moral doctrine manual and his deft way of handling the press". The Times. 17 March 2023. p. 36.

Further reading

[edit]- Kuper, Simon (2022). Chums: How a Tiny Caste of Oxford Tories Took Over the UK. London: Profile Books. ISBN 9781788167383.